Solar eclipses come in various forms, when classified based on their appearance and evolution over the Earth’s surface. We have total eclipse, annular eclipses and partial eclipses. And the boundary case of annular-total eclipses.

All solar eclipses are seen as partial by most observers: at maximum eclipse, the Moon only covers part of the Sun’s disc. During total eclipses, for a small subset of observers located in the path of totality, the Moon is able to fully occult the Sun for a short period of time, never longer than a few minutes. Similarly, during annular eclipses, for a small subset of observers located in the path of annularity, the Moon can be seen silhouetted in front of our star but its size is slightly too small and a bright ring of Sun’s light is left shimmering around it.

Annular-total eclipses are boundary cases, when the initial path of annularity morphs, after a while, into the path of totality which then, again after a while, morphs back into the final path of annularity. This is due to the fact that, during this type of eclipses, the apparent radius of the Moon is almost exactly equal to the apparent radius of the Sun (to within about 1%) and the curvature of the Earth’s surface is able to make the Moon slightly larger than the Sun for some observers (who will experience totality) and slightly smaller for other observers (who will experience annularity).

Annular-total eclipses are of intrinsically short duration but they provide very favourable conditions to image the flash spectrum, as they allow seeing a wider angular area of the lowest layers of the solar atmosphere than during most pure total eclipses. Annular-total eclipses are, on the other hand, rather infrequent. Between 2021 and 2050, there are 19 (pure) total eclipses but only 4 annular-total eclipses: in 2023, 2031, 2049 and 2050. To note, the path of the 2031 eclipse will take place almost entirely over water in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, its very end (where the eclipse will have just reverted to be fully annular) barely touching Panama.

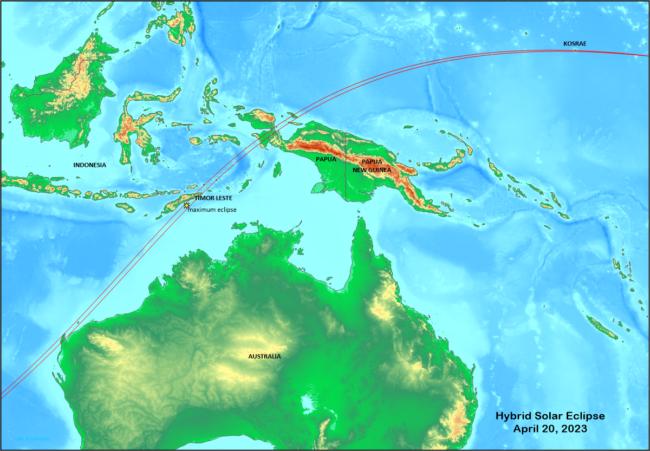

The path of the April 20th, 2023 annular-total eclipse starts as (broken) annular in a remote region of the Southern Indian Ocean near the Kerguelen Islands and it very quickly, over 7-800km, transitions into being total. It stays total, barely touching any land, till it reaches some remote regions of the Pacific Ocean near the Marshall Islands, where the eclipse enters another transition phase into (broken) annularity. The eclipse makes landfall in very few places: in Western Australia, at Exmouth Peninsula, in the easternmost tip of Timor-Leste and through the West Papua province of Indonesia

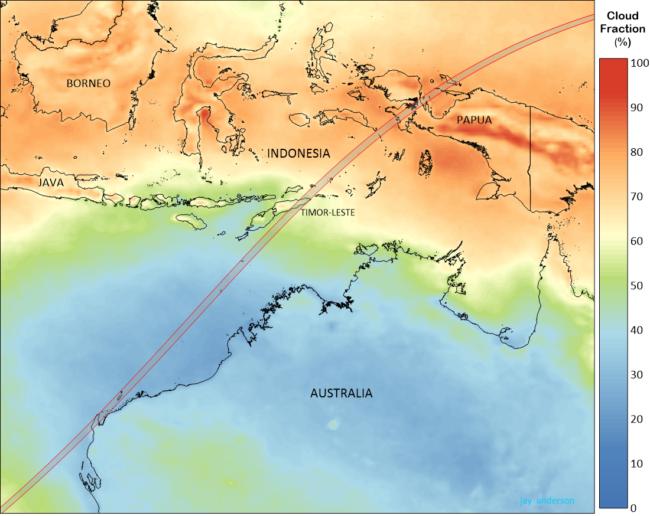

A critical ingredient of any eclipse experiment is to have clear sky conditions. Several things can go wrong with the equipment and its settings but those risks can be managed by properly preparing beforehand and rehearsing the minutiae of the experimental procedure. Even the best laid out eclipse plans can be thwarted by the weather, but a chance to mitigate the risk of cloudy conditions is offered by looking at weather statistics and be mobile.

The meteorologist and eclipse chaser Jay Anderson provides a wealth of weather statistical analyses for upcoming solar eclipse at his wonderful Eclipsophile website. Of the three regions where the eclipse is observable from land, Exmouth Peninsula provides the most favourable statistics, with a mean amount of cloud cover for April of about 30%. This quantity climbs to about 55% in Timor-Leste and to about 70% in Indonesia. No one can know in advance what the weather on eclipse day will be but these statistics provide some guidance.

Usually, mobility would help increasing the likelihood of escaping threatening weather. In the case of the 2023 eclipse, there is little to no possibility of mobility anywhere on land. Due to the fact that eclipse experiments can only be done on land and based on weather statistics considerations, the choice of location to collect time-stamped videos of the eclipse flash spectrum has been locked in to be somewhere in Exmouth Peninsula.